How to Squat with Low Back Pain

Low back pain is one of the most common ailments the general fitness population as well as athletes present with. 80% of people will experience low back pain at least once in their lifetime.

I’ve personally dealt with low back pain and it can be and feel like one of the most debilitating injuries. It can hurt when you lay down. It can hurt when you stand up. It can hurt at rest, with walking, etc.

When dealing with low back pain, many different activities or positions can aggravate it. For the purposes of today’s blog post, if you are dealing with low back pain and it is not improving, make sure to see a licensed healthcare practitioner to evaluate you and come up with a game plan to help you get moving and feeling better.

In today’s post we are going to discuss ways to attain a training effect with the squat if you are dealing with low back pain and/or you have low back pain during or after squatting.

1. Change Bar Position in the Squat

The barbell back squat is considered a staple movement in the gym. It is a great movement for developing strength, power, etc.

It is a very advanced exercise that requires mobility throughout the entire body from the shoulders down through the ankle as well as good control of these joints as well.

There are some people, due to the way they are built or due to their current limitations, that cannot back squat or cannot back squat safely.

Instead of forcing a square peg into a round hole and making things worse, why don’t you try and change the position of the bar.

For example, try Front Squats!

Or Goblet Squats!

Double Kettlebell Racked Front Squats

These variations and many more can be great options to help people with low back pain who want to squat.

2. Decreased Depth

Another option for those looking to squat is decrease how deep you squat. Now, I know this may sound heretical, but it is perfectly fine to not squat to parallel or below parallel.

If you are training for a powerlifting meet, then yes, you need to squat to below parallel for meet requirements. But, for the rest of us who are not training for a meet, it is perfectly acceptable and a great way to get a training effect by squatting to above parallel.

Great options for squatting above parallel are to a box or a bench.

3. Decreased Depth with Increased Loading

To piggyback on my previous point, decreasing depth AND increasing the load.

For example, if you can squat to parallel or below parallel 315 x 5 reps, but experience back pain, maybe try squatting to a higher depth, but with a heavier load?

Try squatting with 325 or 335 to a shallower depth. This would allow for a great training effect while still feeling good by not squatting too deep and potentially contributing to ones low back pain. Training in a smaller range of motion by decreasing the depth can be another great way to train pain-free.

4. Incorporating Tempo Work

Certain positions can be painful because the body, specifically the brain and the nervous system, perceives that position as threatening and unsafe. By putting the body into pain, this is the nervous system’s way of keeping the body “safe”.

Another great way to get a training effect and also train the nervous system that movements are safe is by incorporating tempo work into your routine.

Tempo work consists of:

Slow Eccentrics

Slow Concentrics

Pauses

Slow eccentrics look like this:

Pauses look like this:

Slow concentrics would be performed slowly coming out of the bottom position of the squat.

By incorporating tempo work, you are placing the body under load/tension longer, therefore making the muscles have to work harder. By using these techniques, you will have to lower the load in your hands or on your back in order to perform properly. Plus, it is safer when working with athletes whose main goal is to perform on the field at a high level, not necessarily move maximal amounts of weight.

Another benefit of tempo work is that it is a great way to train the body and the nervous system that positions are not threatening. By going slow and controlled, the nervous system perceives the movement as safe as compared to going quickly through a particular movement.

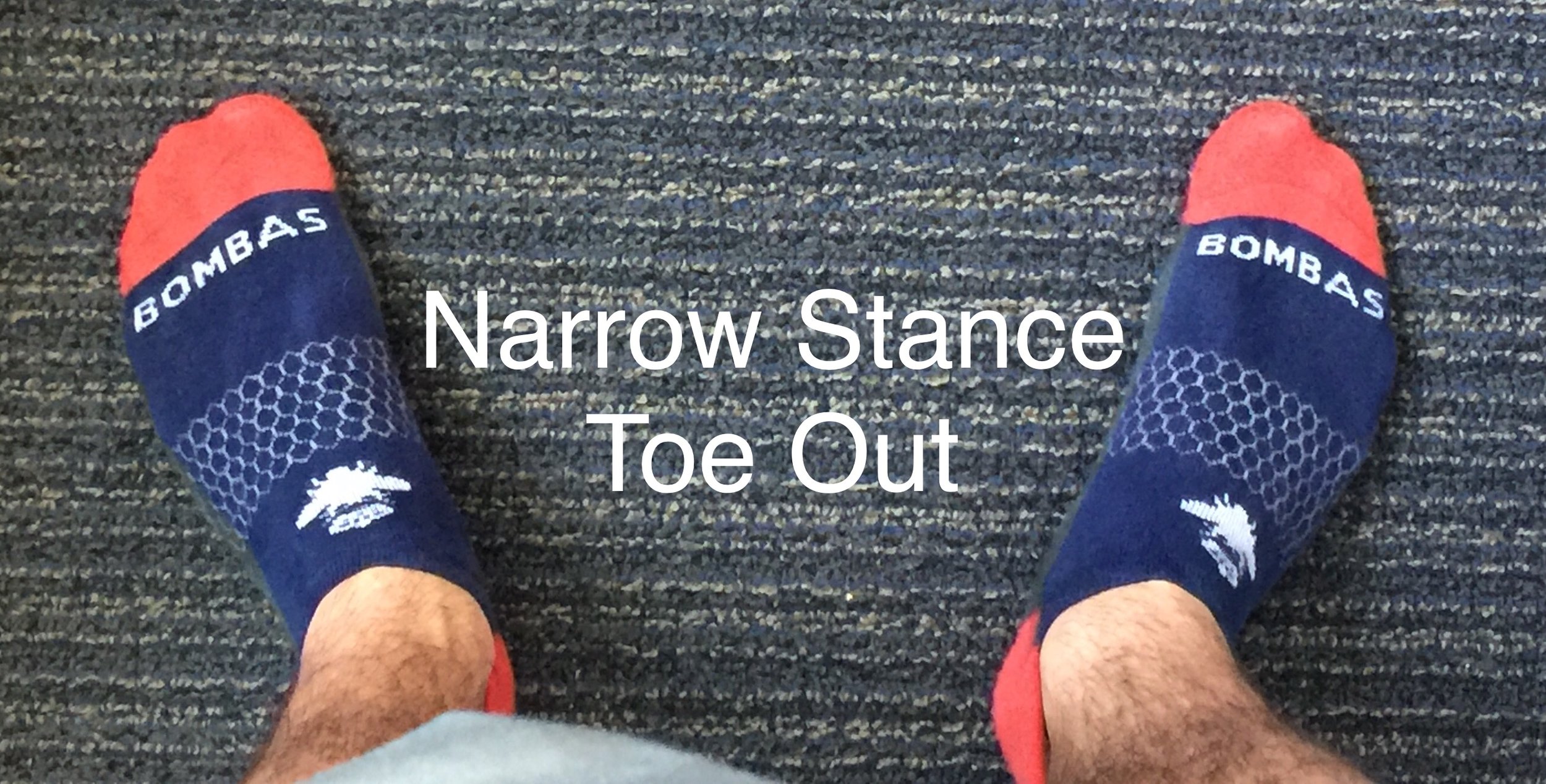

5. Adjusting Squat Stance

Last, but certainly not least, is that not everyone will be able to squat to parallel or below with their feet shoulder width apart and feet straight ahead.

Everyone has different hip structure and shape and due to this, some people will be able to squat feet shoulder width apart and pointing straight ahead while others may need to turn their feet out slightly and/or widen their stance.

Here is a great picture of the differences in hip structure:

photo credit: themovementfix.com

This photo demonstrates the differences in acetabula (hip sockets) orientation on the left in one pelvis compared to another.

The pelvis on the left will have to squat with a potentially wider stance and with their feet turned out while the pelvis on the right potentially may be able to squat with a more narrow stance.

In the picture on the right, this is looking at torsion through the femur (thigh bones). As you can see on the femur on the right, there is rotation from the top of the femur down through as it goes towards the knee. This rotation or “torsion” is going to also contribute to why someone may have to toe out or not be able to squat with a “feet straight ahead” stance.

So, the moral of the story is that if you can’t squat to depth with your feet straight ahead and shoulder width apart, try widening your stance slightly and turning your feet out slightly and see if you can squat deeper and if it feels better.

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

If you are dealing with low back pain and still want to be able to squat, try:

Changing the Bar Position with Squatting

Decreasing Your Depth

Decreasing Your Depth and Increasing the Load

Incorporating Tempo Work

Adjusting Your Stance

Tags:

July 18, 2018